Pre-service educators can visually express their own life experiences through the medium of comics – how can this be helpful?

Encouraging pre-service teachers to reflect on their past educational experiences is a common practice in teacher education programmes. Such reflections can help student teachers explore how their educational philosophy and beliefs have been shaped by their past. These tasks are normally written tasks, but there has been growing interest in more visual methods, often drawing on art-based techniques. Innovations in this area include the use of digital autobiographies and participatory visual methods of image capture and analysis. Building on this tradition, we explored whether the medium of comics could be used by pre-service early childhood educators to construct their life stories, and what this mode of presentation could reveal about what they considered significant and important in their past lives.

Why comics?

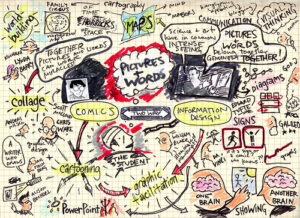

A mention of the word ‘comics’ conjures up images of children’s annuals and cartoons, but this less serious view of comics in popular culture is slowly being replaced by an appreciation of the unique affordances of this medium of expression. Comics exist at the intersection of the visual and the written and offer innovative ways of communicating stories and ideas that neither text nor image could achieve alone. They contain a wide range of techniques to communicate their message.

For example, the positioning of text along with images can exaggerate contradictions and similarities or can be used to emphasise certain aspects of the text or image. There are also a range of culturally and socially recognised visual resources that can be employed by the comic artist. Decisions around their overall layout and design, through the manipulation of panel size and gutter position (the space between panels) can also be used to display (and play on) time and distance. Cause and effect can be suggested through the coexistence of some images with others. A further example of the language of comics lies in the affordances offered by the use of the comic’s gutters. For example, gutters can be used to suggest a series of events between panels where the reader engages in a form of closure filling on the gaps in a story by making assumptions about what occurs between the panels. As well as the range of options for the layout of the comic, characters can be represented in highly realistic images to more abstract forms. Highly abstract representations of characters create greater universal appeal and association, whereas more realistic images of characters represent a more personal narrative not necessarily presented for the reader to associate with. These examples highlight how the complex language of comics provides a multitude of resources for communication and expression.

What is autobiographical memory?

In our study we adopted the theoretical framework of autobiographical memory to explore and make sense of the completed student comics. The memories we have about our past lives are commonly seen as a store of all past experiences that can be recalled to varying levels of accuracy depending on the individual. However, our remembering is a more constructive and fluid process than this implies.

Instead of containing a chronological catalogue of events of our past, what we remember are often the events and experiences that provide continuity and meaning to our life. In this way, what we recall about our life reflects what we consider to be important at the time of the experience and what we consider to be important now at the time we recall it. Therefore, what is constructed from memory is highly dependent on our current priorities and goals, known as our working-self goal hierarchy. Memory is therefore used to maintain the ‘story of the self’, containing important memories that help construct and maintain our life story. These can include significant events that may explain personal decisions and actions or highlight what the person deems critical. Importantly however, what we present as our life stories is socially and culturally influenced. Therefore, what pre-service teachers recall about their past lives and their journey to becoming a teacher will be inevitably influenced by prevailing discourses of what a ‘typical’ childhood is and what a typical education consists of, and these recollections of the past can undergo a level of reworking over time.

Using comics, we were therefore interested in exploring what images our student teachers used to represent their life stories, how education was presented and what story plots were depicted in their comics.

Our study

Our study worked with 128 first-year students on a 4-year undergraduate degree programme in a Spanish university who volunteered to participate. The comics life-story project formed part of an educational studies module and was, in turn, part of an educational innovation project funded by the university of Alcalá.

Within the module, students were introduced to the potential of the comic as a tool in education through a series of workshops. In the workshops it emerged that the students had a poor level of visual communication skills, reflected in their limited ability to decode visual images and their lack of experience in conveying information in the form of images. For this reason, an exercise was proposed that aimed to develop the students’ visual communication capacity by focusing on their own creation of images. The exercise challenged the students to present their life story in the form of a fixed-structure, one-page comic consisting of 16 panels.

We read all the completed comics to identify the main themes and identify the frequency of associated images. Common images we identified included, images of relationships (including images of families, peer relationships and romantic relationships), images of achievements (including images of sporting success, musical achievements, and travel) and, most interestingly, images of education (including images of them as students, as teachers and images of educational achievement). These were categorised as being either negative or positive depictions.

What did we find?

A clear pattern emerged in the frequency of particular images and the locations of them within the 16 panels of the comic. The early panels depicted archetypal family scenes drawing on images of babies, pregnant mothers, and happy families – largely reflecting the manufactured notion of a natural childhood. The middle panels of the comics mainly depicted positive events such as successes in sports, music and educational achievements suggesting that these events hold particular significance reflecting the self-defining moments of their socio-economic group. Travel played a significant role with many comics presenting holidays or work experience overseas in later panels.

Subsequent images used in the comics reflected the gradual maturation and gaining of independence from family that one would expect to see. For example, later panels consisted of images of relationships with peers and romantic partners as the comic progressed. The increase in referencing these particular images coincided with a decrease in images of the family, indicating a move towards greater independence in adolescence. No same-sex relationships were presented.

Whilst some of the panels presented typical lifetime events such as starting school, others appeared to be used to present particular turning points in their lives. A notable feature of these images was a consistency in their representation of educational achievement; hence for this group it could be argued that educational achievement was an important goal (or at least it was presented as so!). However, there were also events that were presented as turning points that were more negative. For example, some comics presented images of family break-up or the death of a family member or negative educational experiences, however these were infrequent.

Representation of teaching and classrooms

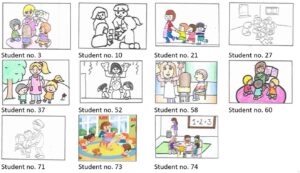

The second aspect of our analysis involved exploring the student teachers’ representations of schools and teaching. A notable aspect of these images was how the type of educational environment differed with age groups and the consistency in the images used to represent classroom practices. When recalling their early experiences of schools or when they were depicting scenes of them working as early childhood educators, they tended to draw on very common images of the teacher (Figure 1). These images highlighted the constructed nature of the image of the teacher drawing on stereotypical images.

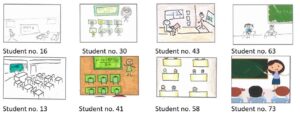

Classrooms from primary school were presented in a more traditional manner with typical items such as blackboards and desks presented in the images. When depicted, the students were normally sitting passively whereas the teacher was in a standing position at the blackboard instructing the students (see Figure 2).

Story plots

Our analysis also looked for the presence of common story plots. There was a common plot evident in many of the comics that commenced with an idyllic family upbringing that was followed by a number of general event memories (typical of childhood that represent rites of passages and self-defining moments in western culture). This period of general positive experiences was normally followed by moves towards greater independence represented by travel, gaining their driving licence, falling in love or graduating from high school. The story normally ended with the student representing themselves as being in university. The overall narratives presented seemed to present their progression to teaching in quite a neutral and uncomplicated way.

What do these findings tell us?

Our study revealed, in a visual form, the homogenous way in which the pre-service teachers presented their lives. They drew on the cultural scripts of the ‘ideal’ family, ‘ideal’ relationships, and the ‘ideal’ educational journey to construct their biographies in a taken-for-granted uncritical way. This homogeneity is not unique to this cohort however as many observers have commented on the dominance of mostly white middle-class entrants to the teaching profession. Embedded within this cohort are views of the family and the importance of education. Such recollections also intersect with one’s views of sexuality, social class, and meritocracy. The self-defining moments presented, such as achievements in music, sport, and dance, as well as opportunities to travel, reflect the privileges of middle-class that may be far from the experience and biographical narratives of their future pupils.

Our study also indicates that the use of autobiographical comics provides a unique window into the value system of students and shows how their completed comics could be used by teacher educators to unearth and question the cultural and social norms that are presented within them, particularly how their narratives have been shaped by the social and cultural norms of their upbringing and their own personal histories. Used in a sensitive and careful manner, the students’ analysis of their completed comics could help them recognise that events that they may believe are universally experienced by all, are instead unique to a particular social or cultural group. Through this they could also begin to recognise how they have privileged some life-events over others and how particular beliefs and values have led to these prioritisations. This in turn can help pre-service teachers to consider alternative story plots to their own lives that are not influenced by prevailing norms and values and to recognise and value of alternative story plots that do not fit with the traditional plots typically depicted by successful students that progress to third-level education (and teacher education in particular).

For further details of the study see: McGarr, O., Gavaldon, G., & Saez de Adana, F. (2020). Using autobiographical comics to explore life stories and school experiences of pre‐service early childhood educators. British Educational Research Journal, 46(5), 1152-1170. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3621

Leave a Reply