Authored by:

Iram Siraj and colleagues

By Professor Iram Siraj, Dr Denise Kingston & Professor Edward Melhuish who are all members of the Department of Education at the University of Oxford

Can staff training be a waste of time and money, or might it be the best investment that any early years provision can make?

That investment depends, of course, on the quality of the trainers and the relevance of the training. If you’ve endured a dreary ‘tick box’ day seminar, you might dread any suggestion of professional development and consider it all an unnecessary distraction. If, however, you’ve been inspired by a brilliant training session, you’ll probably want to grab another opportunity from precious time away from the children to develop your professional learning. But does even the very best professional development (PD) actually make any difference to the children in the setting?

Every early childhood education and care (ECEC) provider has an increasingly tight budget, so providers need a strong reason to spend anything on staff training and professional development. Nobody wants to waste money on a poor course which won’t make a scrap of difference to the day-to-day quality of their provision, but it’s hard to know in advance whether or not the sessions will be useful. There is a glut of training on offer to ECEC staff at the moment, and, unfortunately, much of it is neither evidence based nor delivered, sometimes, by adequately qualified trainers.

A lesson from Australia

Recently, in Australia, the New South Wales Department of Education (NSW, DoE) decided to fund a high-level research project which would investigate this matter. In response to the growing body of international evidence that high-quality ECEC services really do deliver a range of long-term benefits to children and society, the NSW DoE wanted to discover if spending government money on ‘evidence-based professional development’ (PD) was worth it or not. So, it funded the ‘Fostering Effective Early Learning’ (FEEL) study to learn whether a bespoke PD course made any difference to ‘the quality of curricula and interactions in early childhood education and care (ECEC) services’ (i.e. pre-schools & long-day care) in Australia. The results were impressive (See report: Siraj, Melhuish, Howard, Neilsen-Hewett, Kingston, de Rosnay, Duursma, Feng and Luu, 2018, NSW DoE DECEAR-15-35. )

Following a comprehensive literature review, the FEEL team of international academics designed an innovative Leadership for Learning professional development programme for early childhood staff at 90, carefully selected, preschool and long-day care centres across New South Wales. These 90 settings enabled the FEEL team to compare their outcomes across a range of locations, socio-economic advantage indices, National Quality Standard (NQS) ratings (Australian pre-school inspections) and service types.

The FEEL team designed the Leadership for Learning PD to cover the foundational principles of child learning and development (including self-regulation, literacy, numeracy, science and critical thinking), and to feature a cascading model of delivery which would prepare participants to take a pedagogical leadership role in their workplaces – and to share their new knowledge with their colleagues and children’s families.

The FEEL study results show that its PD programme has a strongly positive impact on the quality of practice, in areas of curricular and interactional quality investigated, and that it led to improved outcomes for young children in key domains. These findings indicate the extent and the breadth of positive outcomes which can be achieved through investment in high-quality, evidence-based PD for ECEC staff by highly qualified and experienced trainers.

The Leadership for Learning intervention

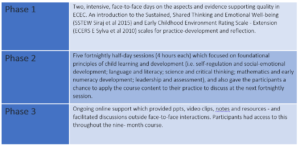

The Leadership for Learning PD programme aimed to enhance the quality of educational and social-emotional experiences for young children in Australian ECEC settings by addressing the knowledge, skills and attitudes of staff in key areas. The programme was developed by Professor Iram Siraj and Dr Denise Kingston after analysing the weaknesses in existing practice which had been detected through a rigorous analysis of SSTEW and ECERS E scores across hundreds of centres from the UK and Australia. In particular, the PD programme focused on improving the quality of interactions with children, on fostering their social wellbeing, and on supporting their concept development within curricula (e.g. maths, language, etc.). The staff training was delivered by Professor Iram Siraj, Dr Denise Kingston and Dr Cathrine Neilsen-Hewett over nine months in three distinct phases:

The FEEL team recruited 90 ECEC centres across NSW, Australia, (with, in total, 1,346 three-to-five year olds) and, before beginning the PD programme, carried out ratings of initial centre quality and child development (i.e. language, numeracy and self-regulation) in all the centres.

Half the centres received the PD in 2016 (the intervention group), whilst the other half continued their usual practice and received the PD in 2017 after the study had been completed (the control group). The team repeated their ratings of quality and child development at the end of the nine-month PD course – before the control group received the training.

During every phase of the PD, the participants evaluated the training and the trainers. They examined their experiences and perceptions of the PD, suggested improvements, explained how the PD was influencing them (or not) as professionals, and whether (or not) they perceived any improvements to quality for the staff, children and families with whom they worked.

What the study found

The FEEL team evaluated the content and delivery of its Leadership for Learning PD by assessing its direct impact on the participating ECEC staff and child outcomes. Overall, the study confirmed that a high-quality, evidence-based, staff training course significantly enhanced the quality of ECEC centres for young children. The 45 ‘Intervention centres’ showed the following improvements:

· changes to pedagogical leadership

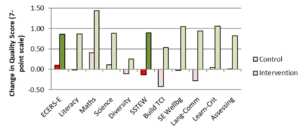

There were significant improvements in the quality of pedagogy (e.g. in early language development, pre-literacy, mathematics, science, diversity) and in interactions (e.g. sustained shared thinking, supporting social-emotional well-being). Specifically, while the ‘control group’ (red/pink bars below) not receiving the training stayed, on average, at similar quality levels over the year, the ‘intervention group’ (green bars below) improved significantly in areas of curricular and interactional quality. The graph shows the change in quality over the year for all quality areas assessed.

· changes to child outcomes

The influence of the Leadership for Learning PD was also evident in child development outcome changes.

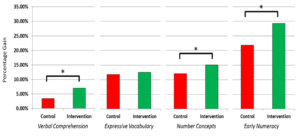

- Children in the ‘intervention centres’ had twice the growth in verbal comprehension as their counterparts in the ‘control group’.

- Their numeracy development improved significantly (more than would be expected in normal development) on two separate measures – 23% greater gains in number concepts, and 28% greater gains in early numeracy.

- They also demonstrated improved socio-emotional development, with a reduction in reported internalising behaviours (i.e. less emotional and peer problems).

- changes to participants

A further qualitative, process-analysis found direct benefits from the PD programme, with the participating staff reporting:

- increased confidence and motivation

- increased intention and sense of purpose in teaching practice, extending themselves to incorporate concepts and ideas covered in the PD programme

- deeper understanding of child development and the evidence base underpinning effective practice

- deeper understanding of their role in influencing outcomes

- improved capacity to share information with families, colleagues, and the broader community

- changes among their children – both in what the children experienced through their own modified staff practice, and also in how the children responded to these new experiences.

The participants described the PD’s impact in terms of children’s increased engagement and motivation, and in improved problem solving and learning.

These changes were, not surprisingly, associated both with course attendance (with those staff attending fewer sessions reporting fewest changes) and also with the degree to which the centres themselves embraced the PD.

The programme expected participants to adopt a leadership role with responsibility for both personal change and change within their teams. Centres which embraced the leadership for learning model of influence most fully (and were intentional and purposeful in their strategies for ensuring all staff engaged in the PD journey) showed the highest levels of growth in environmental quality.

· changes in quality practice

The FEEL staff training programme addressed the need for whole-room or centre change, and encouraged practices and processes which foster developmental outcomes for young children.

81, of the 90, staff surveyed noticed changes among the children in their care through their participation in the PD. They mentioned children being part of smaller groups, being engaged in more meaningful learning experiences, encountering more question-asking and engaging in ’sustained shared thinking’, and generally being much more engaged in their learning:

One participant described, typically:

“Sustained shared thinking – Wow! The other day, while I was involved in a small group activity about measurement, I thought, ‘Is this really happening?’ Through my initial question, the children began supporting and extending each other, and then asked me to lie on the ground to measure objects against my height – before they began ordering them to determine which would be most suitable to retrieve a toy over the fence. I was delighted by the way they worked together in their thinking. As problems arose, all the children were utilised and listened to within the group.”

The participating staff described seeing changes to children’s engagement and motivation, and increased learning and problem solving. 60% commented on children being more engaged; 43% reported children asking more questions; 60% said that their children had become more active problem solvers; and 19% described them as more confident in their interactions):

For example, one participant reported:

“The children are much more involved in their learning, more engaged and interested in discovering new things, and even extending on their prior knowledge. They have taken their learning to a new level that is deeper, where they are eager to use trial and error with things and investigate without being worried about being wrong or right. They show a sense of being proud of their achievements and want to share these achievements with others. Having staff facilitate their learning, they are thinking more for themselves and wanting to do things and discover things for themselves. They are able to think more about their own behaviour and be accountable for their behaviour and how this might influence others.”

Although some participants thought it too early to notice changes, others observed changes within a few weeks. Many commented on how children took charge of their own learning and were more capable of engaging in learning than the staff had anticipated. Several participants commented that “taking a step back and observing children” had made a large impact. A sustained nine-month training programme gave enough time for the participating staff to see the direct link between providing quality experiences and children’s improved behaviour and outcomes.

In their responses at the end of the study, participants noted more changes than at Phase 2 – suggesting greater impact on child behaviour with increased ‘soak time’. The potential longer-term influence of the PD, both in terms of staff practice and child engagement and performance, is captured in the following response:

“Confidence is improving over time, and was the main issue to making changes within our service. Small changes at the beginning, and now we are more inclined to make huge changes across each room. We had staff resistant to change, and eventually lost two of our 26 as a direct result of the changes made.

Three others did not initially see the value in improving the educational practices of staff, but have seen good results over time and heard good feedback, which has resulted in them changing practices and even promoting them now.

Parents’ lack of value in ‘Child Care’ education is beginning to change as we promote our values and beliefs more, and they see the abilities of their children improving. This year would have been better to study the changes in our children, as we feel we have deepened our understanding and improved our practices more and more as time goes by.”

- changes in family engagement

Most staff know that genuine change occurs only when there is consensus and connection across the multiple contexts in which their children operate.

One focus of the FEEL PD course was to ensure improvements in understanding of child development and enhanced pedagogy and practice – with the goal that these would extend beyond the ECEC setting to encompass the Home Learning Environment.

A few participants noted little to no changes for families as a result of the PD. They described not having (yet) received feedback from families, being uncertain how information could be filtered through to families, lacking interest of families, and a work schedule which meant they could not speak with families. Most participants, however, commented that the course had resulted in enhanced connections and increased involvement with their children’s families.

This included sharing ideas, supporting parents in their interactions with their children, parents noticing changes in their children, positive feedback received from families, and an indication that families showed greater understanding of their children’s learning – particularly recognising the staff’s role in their child’s development (i.e. beyond ‘baby-sitting’), and the importance of high-quality early childhood practice.

Some staff noted that they already had strong relationships with their families, and that this had facilitated their efforts to share the new information and learning acquired through the PD. 28% of participants reported receiving positive feedback from parents and providing strategies to engage parents in children’s learning – such as using ‘yarn bags’ to bring home, holding parent information evenings related to self-regulation, and posting information about the PD on the centre’s Facebook site.

One participant reported:

“The importance of self-regulation and informing families of this brought about our ‘Game bags’ idea. Sending a fun family activity home that could cross many areas of development and learning and involve families in thinking about what we all want to achieve for our children.”

The study’s implications

So, what does this mean for the countries in the UK ECEC sector? It confirms what most had already thought instinctively – that sustained, top quality staff training really does make a lasting difference. It shows providers and owners that investing properly in their staff’s professional development is a sure path to a higher quality service. It should help staff to understand the value for them, and their children, of their participation in ongoing professional development.

And, most important of all, it urges providers of training to shape their offerings on the strong evidence of internationally researched best pedagogical and professional development practice.

References

[A .pdf version of this article is available for download here]

Authored by:

Iram Siraj and colleagues

By Professor Iram Siraj, Dr Denise Kingston & Professor Edward Melhuish who are all members of the Department of Education at the University of Oxford

Leave a Reply