Making a vocational programme modular reduces high school dropout – improving students’ employment and earnings.

The ‘dropping out’ challenge

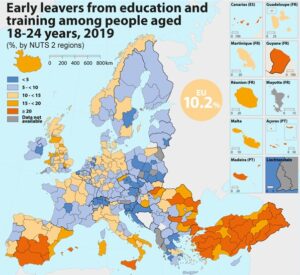

Despite various attempts to improve children’s educational outcomes, high school dropout remains high in many countries. Figure 1 shows, for instance, that one out of four people aged 18-24 have dropped out from high school in Turkey last year, and one out of six in Spain. On average, about one out of ten students do not obtain their high school diploma in the European Union. These average statistics hide considerable differences by region. For instance, although high school dropout rate was 10.9% in the United Kingdom last year, Figure 1 shows that in some Southern regions almost all students obtained their high school diploma, while in some Central regions, almost one out of five students dropped out of high school.

Figure 1: High School Dropout in Europe in 2019 (source: Eurostat).

Figure 1: High School Dropout in Europe in 2019 (source: Eurostat).

Modular education: a possible role

In an attempt to provide effective policy guidance on which measures to take to address high school dropout, we evaluated modular education, a dropout prevention policy that has widely been used in higher education, and has been gaining popularity in secondary education (mostly vocational secondary education). Modular education divides the educational programme into smaller autonomous components or ‘modules’ that bundle a set of learning outcomes (knowledge, skills and/or competences). The completion of each module leads to a partial certificate that can be used on the labour market, and the completion of all the modules leads to a traditional high school diploma. For instance, the programme “hair care” can be divided into many small modules such as “hair styling”, “hair colouring”, and “hair salon management.” The main advantage of modular education is higher flexibity. A student wishing to become a hair dresser in an already established salon would not choose the module “hair salon management”, whereas a student who aims to open a hair salon would. On the other hand, a drawback of modular education could be that students only complete the modules they need for a certain job and leave education prematurely, hurting their long term labour market prospects. Our study provides the first estimates of the causal effect of modular education on high school dropout. Moreover, we also provide correlational estimates on students’ labour market outcomes.

Our evaluation

We evaluated modular education in the Flemish region of Flanders. The Flemish decree of 10 July 2008 introduced modular education for 39% of vocational programmes. The exact modules were provided by the Flemish Ministry of Education and the implementation of the reform was monitored by the government. By school year 2010-2011, 89% of the schools were offering both modular and linear programmes. We used administrative longitudinal data on 95,850 students in Flemish vocational education from 2005 until 2012 and analyzed the effect of modular education on school dropout with a quasi-experimental method called difference-in-differences. The natural approach must be to compare school dropout of students in modular education with school dropout of students in traditional linear education – before and after the 2008 reform and within each school. This is what we did. It is a method that allows exploration of a causal effect of modular education on school dropout.

What our method revealed

Our results indicated that students who followed modular education had a lower probability of dropping out than students who followed traditional linear education. Specifically, students in modular education were 2.5 percentage points less likely to drop out from high school – from a baseline dropout rate in vocational education of 28% in Flanders. This beneficial effect was found for both boys and girls as well as for foreign origin and Belgian native students. However, the dropout-reducing effect of modular education was largest for foreign origin students. In particular, students of foreign origin were 7.7 percentage points less likely to drop out from high school if they followed a modular versus a linear programme. This large effect is particularly beneficial, knowing that the baseline dropout rate for foreign origin students is disturbingly high at 42% in Flemish vocational education. Thus, modular education may be an important policy to enable foreign origin students to catch up with their native peers, without exacerbating the dropout rate of the latter. In addition to high school dropout, we also assessed the influence of modular education on labour market outcomes. However, this analysis was merely correlational, and we could not make any causal claims. We found that modular education leads to a 7.1 percentage points higher probability of finding a job after high school (from a baseline employment rate of 67%), and to 5.5% higher earnings once students have found a job. We found little differences by gender and origin: modular education appears to be beneficial for all subgroups.

Messages from this study

This study shows that modular education is an effective policy to tackle high school dropout and to reduce the ethnic attainment gap in vocational education. Not only are students enrolled in a modular programme less likely to drop out of school, but they are also more likely to find a job and to earn more on the labour market. Therefore, policy makers should encourage the use of modular education in vocational secondary education. Nonetheless, practitioners should pay particular attention to which modules students choose. Students may have purposely chosen for easier modules to obtain a high school diploma and may have fragmented their knowledge, resulting in lower educational quality. Therefore, policy should ensure that students choose compatible modules, by for instance making some of the modules compulsory. Postscript: reflecting on our method Earlier studies were unable to establish a causal effect of modular education on high school dropout, but merely a correlation. This is problematic as children may self-select into programs. For instance, if high ability students disproportionately choose modular programs rather than linear programs, we would erroneously believe that modular education reduces high school dropout. Ideally, we would like to randomly assign students to either a modular or a traditional linear program. However, these types of experiments are costly and are often not generalizable to the large population of students. Moreover, it may be considered unethical to assign students to a potentially detrimental educational program. To tackle this problem, we used difference-in-differences, a quasi-experimental method that obtains causal effects. Essentially, we compared school dropout of students in modular education with school dropout of students in traditional linear education (first difference) before and after the 2008 reform (second difference) and within in each school. This method is especially useful because it obtains causal effects, rather than correlations. At the same time, the results can be generalized to the entire population of students. A potential drawback of difference-in-differences is that it relies on the parallel trends assumption. Namely, before the 2008 reform, the trends in dropout rates in modular and in linear programs must have evolved in parallel. In the manuscript, we empirically assess this assumption and show that it indeed holds in the Flemish vocational education context. The original report of this study is published here.

Leave a Reply